During the Memorial Day Weekend of 2023, while most Americans were enjoying a long weekend, Russian cybercriminals were busy exploiting a zero-day vulnerability in MOVEit, a file transfer tool used by thousands of organizations worldwide. A zero-day vulnerability is one in which the software vendor has had “zero days” to prepare an effective response because they do not know the vulnerability exists. Among the high-profile victims of this attack was Kirkland & Ellis—the world’s largest law firm by revenue—along with BigLaw giants K&L Gates and Proskauer Rose.

A year later, Kirkland found itself named as a defendant in a class action lawsuit, accused of failing to adequately protect sensitive client data. While the full financial impact to Kirkland & Ellis remains undisclosed, breaches of this magnitude typically carry costs in the tens of millions when accounting for forensic investigation, legal defense, client notification, credit monitoring services, and potential settlements—to say nothing of the reputational damage that can’t be quantified on a balance sheet. Just as the firm relied on MOVEit for file transfer, firms rely on API providers (like OpenAI or Anthropic) for intelligence transfer. If a firm fails to monitor the security posture of its AI vendors or lacks a “kill switch” for API integrations during a vendor breach, the liability remains with the firm.

Similarly, in March 2023, Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe discovered that an unauthorized access had occurred on their network starting in November 2022—a “dwell time” of nearly five months. This breach compromised the data of over 637,000 individuals, including clients of healthcare entities, triggering obligations under HIPAA and state privacy laws. The firm agreed to an $8 million settlement to resolve class action claims. However, this apparently low $8 million figure is deceptive; it represents only the settlement payment to the plaintiffs. It does not include legal defense fees, the cost of remediation (forensic experts to expel the intruders and harden the network), the cost of operational disruption, and the reputational damage.

These breaches exploited traditional infrastructure vulnerabilities. But as law firms rush to deploy AI tools, they’re introducing an entirely new category of risk with the same liability exposure—and potentially far greater attack surfaces.

This brings me to the central argument of my work in the legal AI space: the return on investment of privacy is not a regulatory cost center, but a primary asset protection mechanism. The examples above demonstrate that the cost of remediation, litigation, and client attrition vastly exceeds the capital expenditure required for privacy-by-design. And if that’s true for file transfer tools, it’s exponentially more true for AI systems that ingest, process, and reason over your clients’ most sensitive information.

The return on investment of privacy is not a regulatory cost center, but a primary asset protection mechanism.

Although the integration of AI promises to revolutionize various aspects of the legal practice, offering efficiency gains that were previously unimaginable, this operational evolution introduces a risk profile of unprecedented complexity. For law firms, whose currency is trust and whose inventory is confidential information, the deployment of AI systems without a foundational, baked-in privacy framework is not merely a technical oversight—it is a catastrophic financial liability.

In the traditional legal economy, value was generated through the billable hour and the intellectual capital of partners. The proliferation of AI in the legal industry leads to an “AI-driven legal economy,” where the idea of “trusted compute” becomes imperative. Trusted compute means the ability to run powerful AI systems on sensitive data while maintaining absolute guarantees about where that data goes, who can access it, and how it is used, even from the AI vendor itself. Value is now generated not only through the intellectual capital, but also through the ability to process client data without exposing it to adversaries, competitors, or the public domain. Privacy is no longer a defensive posture; it is the production floor of the AI-driven law firm.

Privacy is the production floor of the AI-driven law firm.

The return on investment (ROI) of AI is typically calculated by measuring efficiency gains against deployment costs. However, in the legal context, this formula is dangerously incomplete without a risk-adjusted denominator. If an AI tool saves 1,000 hours of associate time, but introduces a vulnerability that leads to a $5 million breach, the ROI is profoundly negative. The current threat landscape—exacerbated by the proliferation of automated systems like AI agents—suggests that such vulnerabilities are not only likely, but inevitable, especially for firms lacking robust AI governance.

The legal sector faces escalating risk. Nearly 30% of law firms reported having experienced a security breach according to the ABA’s 2023 Legal Technology Survey Report. The average cost of a data breach for professional services organizations, including law firms, is well over $5 million. Majority of law firms reported that these data breaches went undetected by the law firms. These figures represent a critical baseline. For top-tier firms handling mergers, acquisitions, and high-net-worth litigation, the exposure is significantly higher.

These risks will intensify as AI deployment accelerates. Yes, AI can help defenders through autonomous monitoring and threat detection. But threat actors are leveraging the same tools to map networks and automate intrusions in minutes, rendering traditional, reactive security measures obsolete. The asymmetry favors attackers, unless firms build privacy into their AI architecture from the start.

The “Technical Debt” of privacy as an afterthought

I believe that the timing of privacy implementation determines the ROI of AI deployment in law firms. Privacy implemented at the design phase is an asset; privacy implemented post-deployment is a liability. This is not a theoretical abstraction but a quantifiable economic reality driven by the concept of “Technical Debt”.

When a firm deploys an AI tool to “move fast”—especially given the hype—without segregating client data or implementing rigorous access controls, it incurs Privacy Technical Debt. Like financial debt, this accrues interest, paid in the form of operational friction, manual workarounds to protect data later, and in the worst case, the “principal” is called in all at once during a breach.

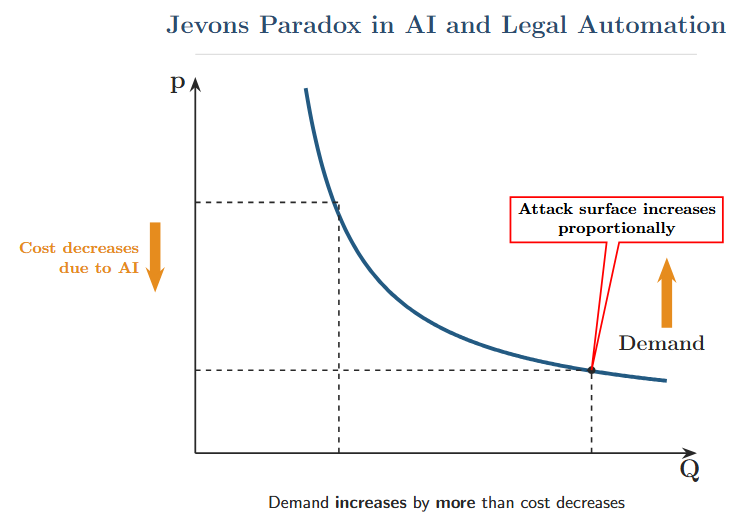

The legal industry is currently witnessing a “Jevons Paradox” in AI consumption. The Jevons Paradox suggests that efficiency gains often lead to higher overall consumption. In the context of legal AI, this means that making legal work more efficient leads to a massive increase in the volume of sensitive data flowing through algorithmic systems. For example, as AI makes document processing more efficient and cheaper, the demand for processing increases, so that firms are processing more data, not less. This exponentially expands the attack surface: if this increasing volume of data is processed through systems with weak privacy architectures, the firm is not scaling efficiency; it is scaling risk.

As AI makes legal work more efficient, firms process more data, exponentially expanding the attack surface (P: price; Q: quantity).

ROI is also a function of revenue protection. Clients are increasingly sophisticated regarding data sovereignty. A law firm that cannot demonstrate a “hermetically sealed” AI environment risks disqualification from lucrative panels. What does this mean in practice? It means Client A’s data can never appear in outputs generated for Client B. It means the AI cannot be trained or fine-tuned on one client’s data in ways that benefit another. It means complete data isolation, auditable access logs, and contractual guarantees backed by technical architecture and not just policy documents.

In an Integris survey 39% of clients stated that they would fire or consider firing a firm that experienced a cybersecurity breach. 37% said they would actively warn peers about the firm, amplifying the reputational damage. Conversely, there is a “Privacy Premium” to be earned: 37% of clients indicated a willingness to pay more for services from firms with demonstrated superior cybersecurity measures. Thus, not only can privacy prevent revenue churn in your firm, it can simultaneously justify a premium pricing model.

The economics of privacy as an afterthought: the 1-10-100 rule

To understand the true cost of privacy failures resulting from a lack of privacy by design, we must look beyond the immediate cleanup costs of a breach and look at the structural economics of software and system deployment. The “fix it later” mindset is a relic of an era when software bugs were merely inconveniences. In the age of AI, a bug in the privacy architecture is a potential existential threat.

The “1-10-100 rule” is a common heuristic in systems engineering that applies directly to AI privacy architectures. It illustrates the exponential escalation of costs associated with fixing defects at different stages of the development lifecycle.

| Development Phase | Privacy Action | Cost Factor | Estimated Cost per Defect* | Implication for Law Firms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements / Design | Privacy by Design (PbD); Vendor Vetting; Threat Modeling | 1x | ~$100 | Identify that an AI tool retains training data. Switch vendors or negotiate “zero retention” clauses. |

| Coding / Development | Implementation of Controls; Unit Testing | 10x | ~$1,000 | Developer realizes the AI output contains PII. Rewrites the prompt engineering layer to redact names. |

| System Testing | Integration Testing; Red Teaming | 15x–20x | ~$10,000 | QA team finds the AI hallucinates fake case law using real client names. Delays launch for retraining. |

| Production (Post-Deployment) | Breach Response; Litigation; Regulatory Fines | 100x+ | ~$100,000+ | Client data leaks to a competitor via the AI. Mandatory notification, class action lawsuits, client exodus. |

* Note: These figures are order-of-magnitude illustrations based on the 1-10-100 heuristics, not empirical benchmarks for law firm AI deployments specifically. The ratios, however, are well-documented across software engineering literature.

Fixing a privacy defect after deployment costs 100x more than addressing it during design. A study by IBM’s Systems Sciences Institute reinforces this, reporting that fixing a bug found during implementation costs 6x more than during design, and up to 15x more during testing. Once the system is live, the costs skyrocket due to the complexity of patching a running system without disrupting business operations, coupled with the external costs of notification and liability.

The math is unambiguous: every dollar spent on privacy architecture during design saves a hundred dollars in breach response, litigation, and client attrition. For law firms evaluating AI deployments, this means the first question is not “what can this tool do?” but “where does our data go, who can access it, and what happens when something goes wrong?”

Kirkland & Ellis and Orrick didn’t set out to become cautionary tales. They were sophisticated firms with substantial resources, caught by vulnerabilities they likely assumed someone else was handling. As AI tools proliferate across the legal industry, every firm faces the same choice: invest in privacy architecture now, at design-phase costs, or pay the production-phase price later.

In future posts, I will explore what privacy-by-design looks like in practice, from vendor vetting frameworks to contractual provisions that give firms real leverage, to technical architectures that make “hermetically sealed” a reality. The goal is not to slow down AI adoption; it’s to ensure that when your firm adopts AI, you’re scaling efficiency rather than scaling risk.